- Home

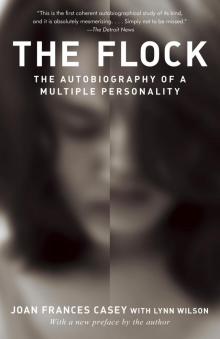

- Joan Frances Casey

The Flock Page 17

The Flock Read online

Page 17

“What do you want me to do?” she asked Lynn. When Lynn offered a suggestion, Jo was often too fearful to do her bidding, and furious with Lynn for her suggestion.

When Lynn responded, “You’re doing fine, just be yourself,” Jo became incensed, sure that Lynn was manipulating her. Jo grew increasingly frustrated, and her frustration frightened us all.

I mentioned to Lynn our concern about Jo, and she tried to reassure me. “Renee, it’s going to take Jo a while to understand that she’s just fine the way she is. That’s part of Jo’s problem. She’s sure that no person could like or accept her for her own self.”

Lynn seemed not to understand the seriousness of the matter. “I want Jo to feel better about herself,” I agreed, “but you know how this kind of frustration has sometimes created new personalities in the past.”

“Now, Renee,” Lynn chided, “you don’t need to create new personalities to please me. I care about all of you and am really happy with the progress you are making in therapy.”

I still felt uneasy. That we didn’t have to create a new personality to please her didn’t guarantee it wouldn’t happen. And I was worried that Lynn wasn’t prepared for that possibility.

Jo warned Lynn in her own way. “If I suddenly changed and became the person you wanted me to be, you wouldn’t even notice that I was really trapped inside,” she accused bitterly.

Jo II, the personality created to be what Lynn wanted, appeared a few days later during a session; to the group’s amazement, Lynn recognized her immediately.

“I know you think you’re doing what you can to keep me happy with you,” Lynn said gently to this personality who insisted she was Jo, “but I need the real Jo to spend time with me and work out her problems.”

DIARY December 2, 1982

Therapy has become intense. In some respects, I’m pleased about what has happened since Jo’s frantic phone call a few weeks ago. I know I’m walking a fine line when I answer Jo’s pleas for help. I don’t want to encourage overdependency, but have found that, when I give her more attention than she’s aware of wanting, I cut through her defenses quickly and cleanly.

Breaking through defenses, however, then increases dependency. It’s good in that this young woman must recognize her emotional infancy before she can grow to be a strong and healthy adult. When some aspect of therapy has particularly frightened one personality or more, I’m grateful for the maternal transference that delivers her to the office every afternoon. No matter how much therapy hurts, she has to see how long it will be before this mother rejects her.

Renee has indicated her awareness of the group’s need for me by applying to Harvard for graduate school. I have little doubt that she’ll be accepted, and equally little belief that she’ll follow through. I don’t think that she is healthy enough to be away from me and from Steve, her only supports. I expect that some dysfunction, expressed through Jo or one of the younger personalities, will block Renee’s plan.

The personalities have given me strong evidence that they want me to help them change their old patterns of defense. I didn’t really expect the group to create a new personality, despite Renee’s and Jo’s warnings. When Jo II emerged, I was surprised at how well she intuited ultimate therapeutic goals. Jo II told me today that her problems stemmed from early abuse. She laid out all the messages I’ve been trying to give the others: “I created the other personalities because I couldn’t cope with the abuse. The other personalities are my internal friends and protectors. They made my psychic survival possible, and I’m trying to appreciate their importance in my life. Once I work out my fears and love all of these different parts of me, I’ll accept them into my own being, and then I’ll no longer be multiple.”

If it were really the Jo personality recognizing all of that, I’d say that my patient was very near recovery. Even so, it is important that recognition of this sort resides in the group belief system at all.

I’ve read literature that has suggested that MPD can be caused by therapists manipulating highly suggestible patients. I’ve thought since the beginning of my work with Jo that this was unlikely, and I’m even more convinced now that I see what a personality created for my benefit is like. While I am encouraged that my messages are getting through on some level, I feel it unwise to offer nurturing or support to the Jo II personality.

I have to reject this new personality firmly to keep more from forming. The formation of a “therapist-pleasing” personality is a danger not only to Jo but to our therapeutic relationship as well. If I were to accept Jo II, as I have the others, they could avoid our work by using an old defense. I’ve got to respond to the needs of the personalities who existed before therapy and simultaneously let the group know that I won’t accept any created for my benefit.

19.

DIARY January 20, 1983

Christmas and the weeks that followed brought a small but significant breakthrough. The Jo personality and I finally agreed on something she could do that would help treatment progress. I suggested that she read the summary I prepared for Dr. Wilbur a year and a half ago. I thought that reading it might help Jo understand my perceptions of our therapeutic relationship. She seemed excited by the idea.

The resistance that Jo might normally have offered was overridden by her ongoing suspicion that I had shared some “professional secrets” with Dr. Wilbur. She was relieved and seemed deeply touched by what I had written.

Jo called me the day after Christmas, her voice brimming with uncharacteristic joy, to tell me that she had read the full twenty-five-page summary and that she loved me, and I spontaneously decided to reinforce the new level of trust and understanding. At my invitation—unexpected and definitely unmanipulated—Jo came to my home that afternoon and spent a comfortable couple of hours perched on a stool in the kitchen chatting with me while I cooked. Gordon was at the airport, and my kids, home for the holidays, were off visiting their friends. With no new people around to intimidate her, Jo was almost vivacious.

I wasn’t really surprised when Renee asked me a few weeks later if my husband and I would like to attend the housewarming party that she and Steve were throwing. I had suspected for some time that Renee might issue this invitation, and I had considered how I should respond.

I know that many of my colleagues would never understand that going to a party at my patient’s house was as therapeutically useful as my other outside-the-office time with her. But, then again, some of my colleagues have trouble accepting that any time outside of the office is therapeutic.

I could tell that my going to the party was important to Renee. And I decided that my attending might help break through the superficial relationship that Renee and I have. If Renee could see that I sincerely appreciate who she is, she might be willing to share some of her weaknesses and fears openly with me.

—

LYNN AND GORDON CAME to the party, and I made sure that I impressed them as the gracious hostess without a trace of pathology. This was, after all, my natural setting.

Gordon was not what I expected. I had assumed that he would be suspicious of me—this patient who took up so much of his wife’s time—but instead he seemed interested in getting to know me. He was deliberate and thoughtful in his speech and actions, preferring to pet the dogs and talk with me in a quiet corner, rather than to mingle with the crowd.

Lynn quickly found some old friends and was engaged in conversation, but whenever I came by, she caught my eye and smiled. I circled frequently among the guests, but I returned each time to Gordon and resumed the conversation, which grew in fits and starts throughout the evening. I learned that night that Gordon was also a high-school teacher and as devoted to his students as I was. When Gordon told me about his “outside” involvement with students who needed special attention, I understood why he didn’t resent the extra time Lynn spent with my group of personalities. Like Lynn, Gordon refused to separate his work from the rest of his life. Personal and career responsibilities merged in

his desire to do what he could for the people he cared about.

“Have you ever sailed?” Gordon asked. He told me of the limitless freedom he felt out on the lake.

I decided that Gordon honestly liked me. “It would be fun to get together with Gordon and Lynn after all of this multiplicity stuff is over,” I thought. “I’d really like to know them as friends.”

Steve and I agreed that our housewarming had been a huge success. He was pleased that more than sixty guests had come to welcome us to our new house. And he had really had fun at this, the first party he had thrown since Sara’s death. I was touched that Lynn and Gordon had come and that Gordon had gotten to know the real me.

A week later, Steve left for Cornell. I watched him drive off with more relief than regret. Now all of the personalities would have the opportunity to function on an internal clock without worrying about meeting external demands. When I got home from work, I could really be off duty. I was determined to spend the months while Steve was away getting to know the others better and beginning to relax the constant surveillance that I had practiced for more than a decade. Jo spent uninterrupted hours reading her political-science texts and reflecting on her own peculiar existence. She decided to keep a journal and began to trust that she’d have time to write in it regularly.

Missy constructed pictures with paper cutouts and curled up contentedly in her rocking chair with a children’s storybook. Rusty puttered in the basement workshop far into the night, making things out of scraps of wood and nails.

Most important, we all had time to think, to reflect, to grow. We began to know our individual selves and the internal others. Since I was in the unique position of being able to monitor what each personality thought and did during its “outside” time, I watched with interest as each personality forged its own self-concept.

Missy, for example, learned to see herself the way Lynn did and decided that she was no longer an unwanted and ugly little girl. If her friend Lynn loved her, she must not be all bad.

Jo as well developed a better self-image. Now that she understood that she shared her body with others, she concentrated on using the time she had without berating herself for “forgetting” or “daydreaming.”

Jo thought of the other personalities as alien forces, which didn’t help endear her to us. However, she did take a certain glee in giving over to us various disliked tasks. She decided that, if the house got dirty or money got spent at times when she wasn’t in control, she’d be damned if she’d clean the house or pay the bills during her precious hours.

Jo’s increased comfort with herself allowed her to ask Lynn some frank questions.

“How does it feel to be a woman?” she asked Lynn one day late in January.

Lynn seemed perplexed by the question. “I know that the male personalities believe they are boys,” Lynn said cautiously, “but, Jo, I thought you knew you were female.”

“I know I’m not male,” Jo responded, “but I don’t really feel female.”

“Well, how do you feel?” Lynn asked.

Jo thought for a moment. “I feel not-male. I feel lacking, not good enough. I thought maybe you could tell me if that’s what it means to feel female.”

“No, my feeling female does not mean feeling that I lack anything,” Lynn said confidently, and then stopped. “I’ve never thought about how to express this,” she confided. Jo smiled at Lynn’s hesitation, and the therapist smiled back.

Lynn tried again. “Being female is more than biological apparatus, certainly,” she said, “but I’m not sure that I can explain how it feels to be a woman. Let me think about that.” She paused, lost in thought, and then brightened. “Let’s start with your perception of physical self,” Lynn said. “What do you notice when you look in the mirror?”

Now it was Jo’s turn to be perplexed. “I can’t see myself,” she said.

“You what?” Lynn asked, incredulous.

“I can’t see myself in a mirror,” Jo explained patiently. She thought Lynn already knew this. “The last time I remember seeing my reflection was when I was a very little girl. My mother made me stand in front of a mirror and told me I looked retarded. I’m sure I haven’t seen myself in at least fifteen years.”

Jo saw disbelief in Lynn’s face.

“What happens when you look in a mirror?” Lynn asked again.

“I lose time,” Jo said. Then she tried to explain further. “The same thing happens when I look at photographs of myself. I can only guess at how I look.” Her thoughts wandered for a moment. “There are so many things I haven’t done for so long.” She sighed. “Do you remember that afternoon when you took Missy to the park?”

Lynn nodded.

“I floated to the surface for a minute or two while you and Missy were watching the ship. It wasn’t long, but I cherish that memory. I’m sure that it has been a dozen years since I had time outside on a spring day.”

Lynn began to understand how much she had taken for granted. She and Jo worked together to locate the faulty assumptions and to puzzle over questions raised by Jo’s special life: Is it possible to develop gender identification without social cues? If Jo could be knowledgeable with so little experience, didn’t that prove that thinking was more important than living?

Jo worked to open herself up to Lynn, but realized paradoxically that, the more she did, the more dependent she felt. This frightened her.

“The time I spend with Lynn,” Jo wrote in her journal, “is even better than the time I spend alone. I know it’s not right to depend on another person this way. When I count on Lynn to make me feel good, I’m using her as an object. It’s better to avoid people than to use them.”

Jo couldn’t help being so rational and so rigid. She regretted that the guilt brought on by her intellectual understanding made her push Lynn away as surely as she was drawing Lynn near. With a logician’s distaste for inconsistency, Jo tried to make sense of her ambivalent feelings and behavior.

“I know Lynn cares,” Jo wrote.

I know that she helps me. But I’m not ready to be cared for, to be helped. Lynn undermines the comforting distrust of people I’ve built up over the years.

Lynn makes my life fuller by being someone I can depend on, but she also makes my life more complicated. I don’t know how to deal with a person who really knows me and who treats me consistently based on my actions alone. I don’t know how to deal with a person who understands that the other personalities are not me.

Whether I lose five minutes or two weeks of time, Lynn knows me when I return and accepts that I am unaware of what has happened. I resist Lynn’s acceptance and understanding. I deny the reality of Lynn’s caring and pull into myself. I don’t want to do that to the one person who has known and loved me for myself, but it’s like trying to tell a turtle not to retreat into his shell. It’s the only way I know how to live.

DIARY February 10, 1983

Jo and the rest of the group have done well, so far, with being alone in the house. I’ve seen a real change in therapy.

Renee shows continually increasing interest in the others and willingness to help with “their” treatment. She now displays an exasperated parental attitude and protectiveness toward them that is very different from her previous disdain and embarrassment. Renee would still deny that she has any vested interest in therapy, and I have no need to challenge her. I am content to see that her tolerance of the others is growing and that, more than ever before, she feels comfortable using time at sessions to discuss concerns of her own.

Missy is thoroughly enjoying the hours she spends with me. She openly soaks up my admiration and appreciation for her many delightful traits and her special ways of seeing the world, which only annoyed and disconcerted her parents.

Joan Frances continues to avoid the whole situation as much as possible and rarely appears in my office. But it is probably a step forward that she pops out occasionally to plead with me to make her worthy of her mother’s love. She disappears the

minute I suggest that Nancy’s view of her may not be the most valid, but she comes back at a later date to hear the same message.

It is with Jo, again, that the storm is brewing. She has strong primeval feelings and absolutely no tools to cope with them aside from intellectual denial and amnesia. For brief periods, she trusts me enough to engage in theoretical discussions, and she seems at these times truly delighted. But then she feels guilty for her joy.

Until quite recently, the relationship I had with Jo held no meaning for her. It was merely a task that she carried out. But now she cannot deny my caring and, worse, she now cannot deny her love for me. Since Christmas, Jo has seemed increasingly distraught about her inability to acknowledge that she might have been abused. Treatment itself has become a trap, in the sense that she knows a time is coming soon when she won’t be able both to continue therapy and to continue to deny the abuse. But she admits neither to feeling trapped nor to her steadily growing anger.

The anger is uncomfortable for both of us, but I see it as my ally. It is creating pressure. Memories of abuse are beginning to “bleed through” to Jo from other personalities.

I continue to push her, even as I offer constant support. And I am prepared for Jo to misunderstand my allowing her pain to persist. Inevitably, she will blame either herself or me and lash out at one of us. This is a dangerous period in therapy, but if I can be prepared for any crisis that might come, our work should reach a new level.

—

WITHIN A FEW WEEKS, the time of comfortable, theoretical talk for Lynn and Jo was only a memory. Therapy had become what Jo called an adversary relationship.

“Jo,” Lynn said, “you have to hear about how you were abused. You have to think about it rather than dismiss it.”

Jo claimed the other personalities were lying. Her father loved her, even if she wasn’t the boy he wanted. Her mother may not have really loved her as she wanted to be loved, but Jo didn’t think that absence of love amounted to abuse. “I was a difficult child,” she explained to Lynn. “I hated being small and ignorant, and I’m sure that I made life difficult for everyone around me.”

The Flock

The Flock